Dr. Debby Hershman, Deputy Director and Chief Curator at Large, one of the founders of the Biennale; Henrietta Eliezer Brunner, Chief Curator of the Biennale, and Chanan de Lange, the exhibition designer, share with you the story of the first Tel Aviv Biennale of Crafts & Design – an innovative museum project that binds together creative fields and forms of material culture, rupturing the boundaries of disciplines and mediums.

Dr. Debby Hershman – Deputy Director and Chief Curator at Large, one of the founders of the Biennale

The Biennale, which extends throughout the museum galleries, displays, and outdoor spaces, presents, for the first time, a contemporary picture of the intersecting worlds of craft and design – with an emphasis on ceramics, glass, jewelry, textile and paper – interwoven together. The 2020 Biennale, titled First Person. Second Nature, features some 250 works: sculptural and design objects, artworks, site-specific and outdoor installations, video and sound works, performances and collaborative projects.

Held in collaboration with the Israel Designer Craftsmen’s Association, academic institutions and the Tel Aviv-Yaffo Municipality, the Biennale features 300 Israeli craftspeople and designers, product designers, fashion designers, multidisciplinary artists, and architects, including academic research programs: the MA program in industrial design at Bezalel; CIRtex – The David & Barbara Blumenthal Israel Center for Innovation and Research in Textiles at Shenkar; and miLAB – the Media Innovation Lab at the Herzliya Interdisciplinary Center.

As part of our mission of artistic renewal, we at MUZA seek to reinforce and reshape the museum’s identity as a unique site, dedicated to the presentation of material culture as a representation of local culture. This sphere has been given expression in craft biennales held at the museum over the past 20 years, which were dedicated to various materials. As we proceed into the 21st century, we aim to embark on a new path, which will lead us to a new definition of contemporary craft and design: a bold initiative binding together all of these fields and illuminating the local Israeli scene.

In order to fulfill this vision, we have conceived of the Tel Aviv Biennale of Crafts & Design in the spirit of the contemporary, global artistic tendency to rupture the boundaries between different fields. We believe that this approach is also relevant to the presentation of material culture, due to the fact that the fields of crafts and design operate today in shared contexts, as evidenced both by their engagement with new technologies and by their sources of inspiration and creative stimuli, which affect each other and are influenced by one another.

In order to realize this daring project, we needed a professional “dream team.” For the creation of the Biennale, one of the most comprehensive and challenging museum projects undertaken in Israel, we chose some of the country’s most highly qualified curators, designers and museum professionals.

The Biennale designer, Chanan de Lange, one of Israel’s leading designers, a senior lecturer at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, and an active artist whose works are featured in solo and group exhibitions, was the ideal designer and artist to take on the challenge of such a large-scale exhibition, which is also a work of art. The graphic designer, Koby Levy, is a prominent designer and lecturer in the field of visual communication and cultural branding. The exhibition installation was executed by Omri Ben Artzi – Studio OBA, who specializes in the design of multidisciplinary exhibitions and displays, including art and archaeology exhibitions.

The works on display in the Biennale represent different mediums. They range from small-scale metalsmithing works to monumental installations, video, sound and performance art, as well as from laboriously created manual crafts to works created by means of cutting-edge technologies, which bring together craft, design, and contemporary art.

The result is as beautiful as it is insightful and alluring, and the exhibits come together to form an intriguing museal and cultural narrative. We at MUZA hope that the breadth of this exhibition will serve as a magnet for a large and heterogeneous audience, while turning an empowering spotlight on contemporary Israeli craftspeople, designers, and their works.

About the Curatorial Process

Henrietta Eliezer Brunner, who led and coordinated the work of the curatorial team – accompanying the Biennale of Crafts & Design from its initial conception to the mounting of the exhibition, moments before Israel’s first COVID-19 lockdown – presents the exhibition.

Henrietta Eliezer Brunner – Chief Curator of the Biennale

The Biennale brings together, for the first time at the museum, various manifestations of contemporary craft and design, while seeking to map their scope, identify similarities and differences between them, and point out new paths and directions. In its “multidisciplinary” approach, the Biennale seeks to blur familiar boundaries and undermine existing hierarchies between mediums and media.

Craft and design function like communicating vessels, exchanging roles or even merging together. Whereas craft, which is based on empirical knowledge, gives rise to one-off artifacts, design is considered to be closely connected to industry and mass production. Both, however, revolve around material knowledge, are closely linked to science and technology, and are attuned to their environment and to the social, political and economic processes taking place in it. Operating in common contexts, they nourish and respond to one another.The Biennale allows for a number of connections. The title of the exhibition, First Person. Second Nature, refers to the same unmediated physical, emotional and mental connection between the creator and the medium, as a means of self-expression and a habit that becomes ‘second nature,’ a driving force and an inner compass. The 250 works and projects showcased at the Biennale were divided into five thematic chapters. First Person/ Second Nature, which lends its name to the title of the present Biennale; Need/Must, a play on words borrowed from Li Chen’s work, in which she uses the commercial medium of neon signs to convey ambiguous messages based on the urgency of constantly changing needs to create and consume; You are here, inspired by the common expression used to indicate our location on the map, assembles works that address local issues and narratives; Heaven (and) Earth brings together the physical, earthly and spiritual aspects of our world, and seeks to capture nature’s harmony and vitality, whereas “matter” serves as a starting point – either as a physical, virtual or metaphorical presence; finally, Back to the Future features works that share a conscious affinity with tradition, which is supplemented by new layers of interpretation arising from the encounter with innovation and technology.

The connection and affinity to the past is realized in a variety of ways. Nearly half of the works extend throughout the museum’s permanent displays and outdoor sites. Many of them respond to, and correspond with, the museum’s collections, architecture, geographical location and its history. For example, Avner Sher‘s cork towers, located near the ancient Philistine city of Tel Qasileh, not far from the vestiges of the Palestinian village of Sheikh Muanis, and overlooking the Tel Aviv skyline, serve as silent testimony to the history this site. Some works ‘intervene’ within the intimate space of museum displays. Hila Amram‘s installation, for instance, creates a visual and cultural shock by planting mass-produced consumer products with a synthetic rose scent among ancient Islamic rosewater vials. In this manner, she raises questions about the culture of consumption and abundance, the loss of the object’s importance, and its reduction to its basic function. Other works refer to the symbolic power of the ancient exhibits: for example, Shir Handelsman‘s videowork, in which the artist staged a vocal performance that takes place in the sky: a martyr (male opera singer) pleading to unite with his Creator adds a spiritual dimension to the inanimate exhibits of the Ceramics Pavilion. All of these ‘interventions’ shed new light on the historical artifacts, which can now be viewed not only as relics of bygone eras, but also as expressions of a living and evolving material culture.

The connection between design, science and technology is expressed in the transformation of the studio into a research laboratory that reflects interdisciplinary work practices characteristic of numerous contemporary fields of knowledge and creativity. The Biennale will provide a unique behind-the-scenes look at the thought processes and design research of four academic bodies: the Master’s Program in Industrial Design at the Academy of Art and Design, Bezalel; The David & Barbara Blumenthal Israel Center for Innovation and Research in Textiles (CIRtex), Shenkar; The Media Innovation Laboratory of the Herzliya Interdisciplinary Center (miLAB); and the Material Flow Collective.

The Observation Tower and “The Case of Selective Breeding,” Master’s program in Industrial Design, Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design. This program is hosted on the second floor of the Migdal Gallery, overlooking Tel Aviv.

On the Design of the Biennale

The first Tel Aviv Biennale of Crafts & Design, held at the Eretz Israel Museum, covers an extensive area throughout the museum grounds. The design of the Biennale involved numerous challenges, including the choice of a display style, design and material language, the creation of the atmosphere and the engagement with the exhibition’s contents.

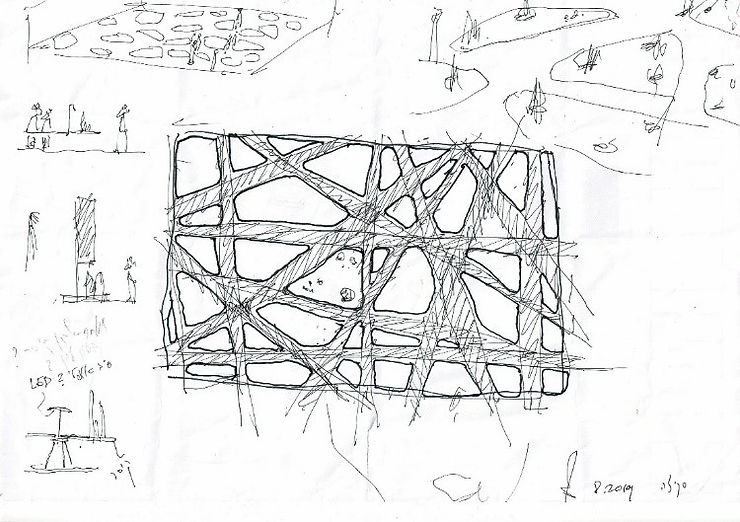

Chanan de Lange – On the Design of the Biennale

The design of a biennale differs from that of a regular exhibition. The current biennale is exciting and challenging. It is unique in terms of its contents and scale, as well as in terms of its status as the first biennale to bring together craft and design – a tradition in the making. The design process began with an in-depth study of the selected works and intensive meetings with the curators. We later toured the outdoor museum areas, the permanent displays, and the temporary exhibition galleries. I reached the conclusion that the exhibition should be composed of different spatial design languages. This was the basic assumption that gave rise to the various solutions. I saw no need to impose a uniform language on the entire Biennale. I drafted general outlines, yet each exhibition space was given its own design “personality,” based on its specifications and the works on display. The proposals addressed curatorial, conceptual, and material concerns, alongside movement through space, lighting, and so forth. At the same time, each area or exhibition space gave rise to different ideas and sketches. Despite the curatorial freedom accorded to the different disciplines, the design approach had to successfully lead the visitors through the different exhibition spaces, so that the spatial experience of each display would be enjoyable, legible and clear.

In the large Rothschild Gallery, for instance, the idea was to create open thematic sections. The design plan created an “urban” space arranged at different heights, allowing for free movement among suspended metal surfaces that hosted several works, so that every work acquired its own territory. The entire space is open, without dividing walls, so that visitors can identify their location and their movement is intuitive. For this space, I chose dark walls and focused lighting so as to grant each work its autonomy, despite the open expanses. The viewers move along “streets” that contain “squares,” with a large-scale work located at the end of each street. For example, the work by Murjan Abo Deba, in which she “battles” the sea waves with a floor squeegee, is revealed to viewers as they enter the exhibition, and serves as a magnet at the end of one “street.” The most important decisions, for me, beyond the thematic clusters defined by the curators, were the location of each work in the space and the musical resonance it creates with its “neighbors,” so that each display area is also a small exhibition in its own right.

In the Observation Tower, the design follows the principle of the classical White Cube – white walls and a bright, light-filled display, in accordance with the works chosen for this space.

In the permanent display spaces (Glass, Ceramics, Man and His Work, and the outdoor sites), the design did not change the existing spaces, but rather was integrated into each one of them in a manner compatible with its character, following the Biennale’s concept. There is something inert and lifeless about the idea of a “permanent display,” which creates the sense that nothing ever changes. When you revisit a museum that you have visited the past, you are almost certainly going to skip over the permanent exhibitions. The moment a museum opens its permanent displays to new up-to-date, changing interventions, these spaces once again awaken curiosity. A permanent display can host contemporary artists from a range of fields, who are usually happy for this opportunity for dialogue. Such interventions can take place in parallel to existing exhibits, or create an entire new layer, that changes or even disrupts the permanent display.

The Glass Pavilion, for example, which features the ancient glass collections, is hosting contemporary works such as the site-specific installation of light and matter by Lila Chitayat, or Andrey Grishko‘s work, which responds to Ennion’s Blue Jug – an ancient glass masterpiece dating to the first century CE – which is replicated using a 3-D printer, while revealing what was lost with each act of replication. The contemporary world of technology is experiencing a hunger for craft. Computer screens and the technological potential of AR (Augmented Reality) and VR (Virtual Reality), computer games, and more, alongside 3-D printers that make use of various types of solidifying materials, have created a new interface. Makers in different fields are forging encounters between craft and these new materials by means of technology. Today’s accelerated technological development is creating a counter-reaction, as materiality and even ancient technologies are resurfacing in contemporary discourse. At the same time, designers who are not affiliated with the world of craft are searching for contact with primal materials. This is currently a popular trend, which may take a new turn in the near future, in accordance with changing circumstances or far-reaching technological innovations.

More Articles

New Acquisitions: Gifts from the Tennenbaum Collection to the Glass Pavillion Over 70 glass items from the Rivka and Zvi Tennenbaum Collection have been donated to the Glass Pavilion in memory of their son, the flute player Yadin Tennenbaum, who was killed at the Suez Canal in the Yom Kippur War

18.04.24

New Acquisitions: Works Exhibited at the Biennale of Crafts & Design Some 60 artists whose works were exhibited at the Biennale of Crafts & Design held at the museum in 2020 and 2023 generously contributed their works to the collection of MUZA, Eretz Israel Museum, Tel Aviv

18.04.24

International Conference: DAY 1 – movies and lectures

24.01.22