Organism 144 is the product of a sociocultural discourse conducted through – and concerned with – art and design. This discourse has evolved between the members of the Material Flow Collective, which is composed of 12 designers, creative artists, and lecturers on art and design. Each group member wrote a personal manifesto representing a personal stance concerning environmental issues. Twelve objects, the first “parts” of this organism, were created in conjunction with the manifestos, serving as the basis for the organism’s growth. This process gave rise to a conversation between materials and ideas, in the course of which the group members responded to one another’s works, while attending each time to a different group member: 12 times 12 equals 144.

Material Flow Collective members: Ariel Lifschitz, Assaf Krebs, Ayelet Karmon, David Spectre, Eyal Schoenbaum, Maya Arazi, Michal Fraifeld, Ofir Liberman, Orit Freilich, Tal Kamil, Rakefet Kenaan, Yuval Etzioni

A Conversation with Rakefet Kenaan on Design Actions Undertaken in an Environmental Spirit

How was the group formed?

The group came together organically, it wasn’t really planned. It all began in the context of an academic study, in which I interviewed lecturers at Shenkar who engaged with social-environmental issues, in an attempt to better understand the professional and pedagogical themes they were concerned with. At a certain point, I felt that theoretical discussions were not enough, and since all the people I interviewed are also designers and artists, in addition to being lecturers, I invited them to engage in some form of action in the spirit of the environmental issues we had discussed.

The idea of shared/collaborative action echoes environmental ideas and ways of ecological thinking, which are systemic and interrelated. Nothing in our world is truly autonomous or self-sufficient. This is true both of us humans, and of the entire biosphere in which we live. It all functions within systems. Everything and every action are always part of a system, and are simultaneously influencing and being influenced.

How long have you been working on this shared project? How does one maintain the continuity of the process when working on such a project?

In early 2017, we began meeting every two months or so. We consolidated a work process in which each group member transmitted a “material” to another group member, and each of us performed some sort of action with the received “material.” These materials included all sorts of things: ranging from physical materials, such as a palm frond, squid bone, ball of textile, liquid nutrients for plant roots or a mouse trap, to assignments such as going to the beach for an hour, observing the environment, and returning with insights, or scheduling a personal meeting with a leather trader

The rationale behind these transmissions was to enable each of the group members to pursue their individual interests, while operating in an intersubjective sphere shaped by the thinking and involvement of others, who thus become collaborators in creating these individual actions. In this manner, individual actions are preserved while giving rise to a group interaction. This mode of action was revealed to be fascinating, catapulting the participants into new realms of creativity and development, while creating a unique group DNA.

We named our group the Material Flow Collective, a name that describes the concrete actions we engage in, while referring to a metabolic action of absorbing, processing and producing energy; it’s a term whose essence defines life and represents the process of melding, mixing and interaction among the participants and their works, which continues to grow and develop in our work. When we were invited to participate in the Lab project that is part of the Biennale of Crafts & Design, we tried to think of a strategy that would reflect the environmental ideas shaping our work, and especially our work process and the group interactive story. The project Organism 144 was especially conceived of for the Biennale Lab.

Why did you choose to base your project on manifestos?

Organism 144 seeks to reflect the main principle guiding the work of our group and of (natural) organisms more generally: one the one hand, a concern with individualism, self-management and taking personal decisions, alongside constantly influencing and being influenced by the environment (while focusing on the group environment in this case). The choice of manifestos was meant to catalyze the individual work processes of each participant, enabling each of us to express the concerns that preoccupy us in an environmental, social and cultural context, conversing in this way with others and create/structure a broad group discussion.

Did the responses to the works emerge freely? Did everyone end up responding to everyone?

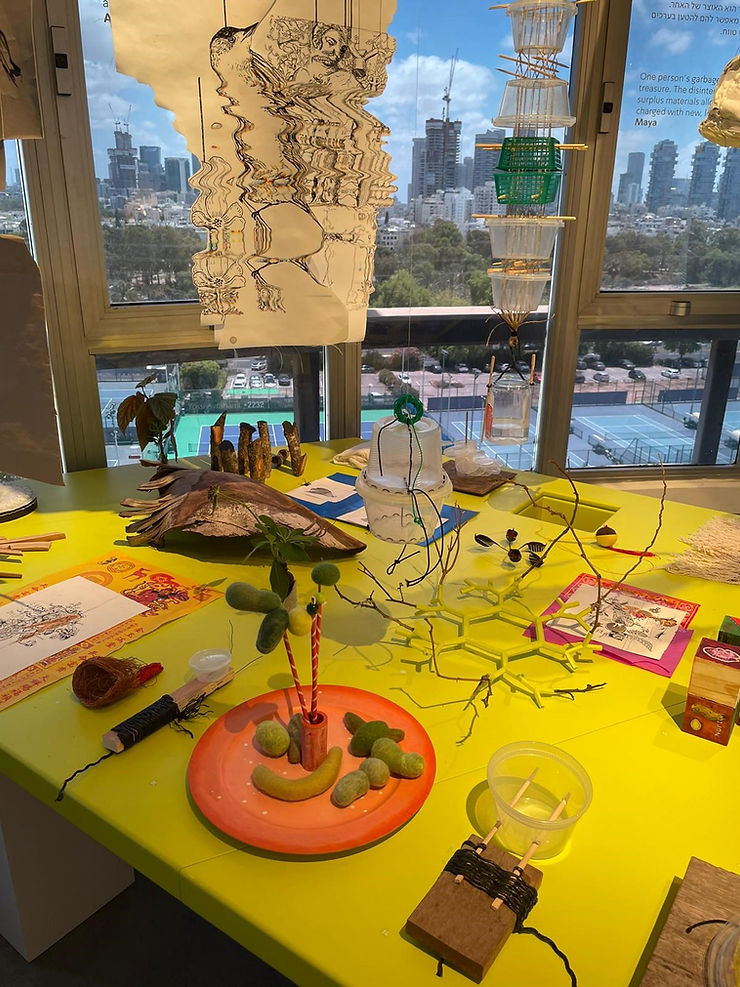

The work process was totally free, in every sense. Some group members did not respond to others in a direct, conscious manner, pursuing instead their personal interests. In certain cases, it seemed that some participants only responded to themselves, yet in the end the mutual influences are evident in all of the objects. We found ourselves reflected in one another’s works in different ways. Over time, this process of melding was given expression conceptually, materially, formally, and technically, in terms of our thought processes and collaborations. As the exhibition opening drew nearer, we gathered together all of the objects, becoming conscious of the palette that seemed to have created itself, presenting a harmonious arrangement of textures, colors and material qualities.

It is interesting to note that although one of the quintessential characteristics of the group is its multidisciplinary character, at no stage was anyone asked or required (consciously or unconsciously) to work in a language or technique reflecting a specific area of specialty. Generally speaking, the structure we created – 12 times 12 – offered a conceptual framework that one could built on or break. As such, it remains a skeleton that supports all of the diversions from it and the spaces created within. Not everyone responded or had time to respond to everyone else, and not everyone created the same number of works. One member did not create a single work, yet his absence was present in the group matrix, and to a certain extent even underscored the active stance of the other group members.

One could state that our entire group process represents a quest for a new way of working. It’s about the creation of a work arrangement that is not concerned only with weighing, measuring and counting the number of objects, but also with the formation of interactions and the value created by presence, or absence, in the verbal discourse – no less so than in the material discourse. This notion of presence encompasses collaboration, raising awareness, and being sensitive and attentive to new concerns, which developed during the meetings and continue to resonate. The group has created, and seeks to continue creating, a process of learning based on reciprocal listening and action. This message appears more relevant than ever in the harsh reality of war and social conflicts currently pervading our experience.

Creating a sense of human awe towards the world’s flora and fauna. Sanctifying nature in order to preserve it.

Tal

Fusion between the natural and the artificial as a healing power that produces a dialogue between humans and their environment.

Michal

Beyond the manifestos (the content), in what way has your environmental approach been given expression in this project?

Our environmental approach is given expression, above all, in our work process as a collective, and in our attempt to follow the principles of Ecological Thinking and function as a system, and as a subsystem in a world full of systems and related organisms.

It is also given expression through manifestos and objects, and through the attempt to underscore, for instance, the need for circular thought processes as expressed in Tal’s works (The Tree that Comes in My Place, or Growth Shroud), as well as in Maya’s compost t-shirts or the view of death as necessary for existence in Ophir’s work (Dead Bird). This work responds directly to Orit’s work Ultra-Sound Bird, yet this elegy for the bird that once lived on a destroyed Earth also echoes Tal’s ideas, and her concern with the loss of nature and the need to worship it in order to save it. The use of available, accessible, biodegradable, used materials and/or waste or leftovers is present in all of the group members’ works. For instance, Yuval’s works make use of leftovers and waste, and function on a conceptual, critical plane while endowing these materials with a new life, new uses and a new aesthetic based on waste. Another example is Eyal’s discovery of the remainders of palm fronds, which he uses as a raw material and source of inspiration for a local sociocultural action, which involves the production of spoons out of palm fronds by the members of Kibbutz Eilot, which grows dates. Or Maya’s use of old T-shirts as the basis for the creation of a new visual language by reassembling old items, or her involvement with compost, which is concerned with disintegration and dissolution, themes that also appear in Tal and Ophir’s works. Orit wanted to work with sound, in order to avoid introducing another physical material into the world, and emphasized the element of listening. Some of her works also involve the use of concrete materials, yet it is always minimal and based on readymades in her immediate environment. Assaf’s works were also created in his immediate environment – old drawings he made himself, drawings on leftover bits of paper and packaging, or readymades.

In Michal’s work, one can see a direct reflection of her manifesto, which called for a healing interaction between the natural and the artificial. This approach is present in all of the objects she created, and can be seen as a sort of invitation to create a hybrid future for humans and the environment. This idea also corresponds to Ophir’s approach concerning the need to create a collaborative, non-exploitative relationship between humans and machinery/technology, as offering a possibility for more moral human field of action.

We produce too many material, objects. As designers, we are responsible for their design. Immateriality is the point of departure for attending to design without materials.

Yuval

One person’s garbage is another’s treasure. The disintegration of surplus materials allows them to be charged with new, long-term values.

Maya

Anthropocenic humans have an epidermis in place of a soul. We live in an age in which the surface is celebrated at the expense of deep structures, the outer peel replaces the core, and the symptom replaces the content.

Assaf

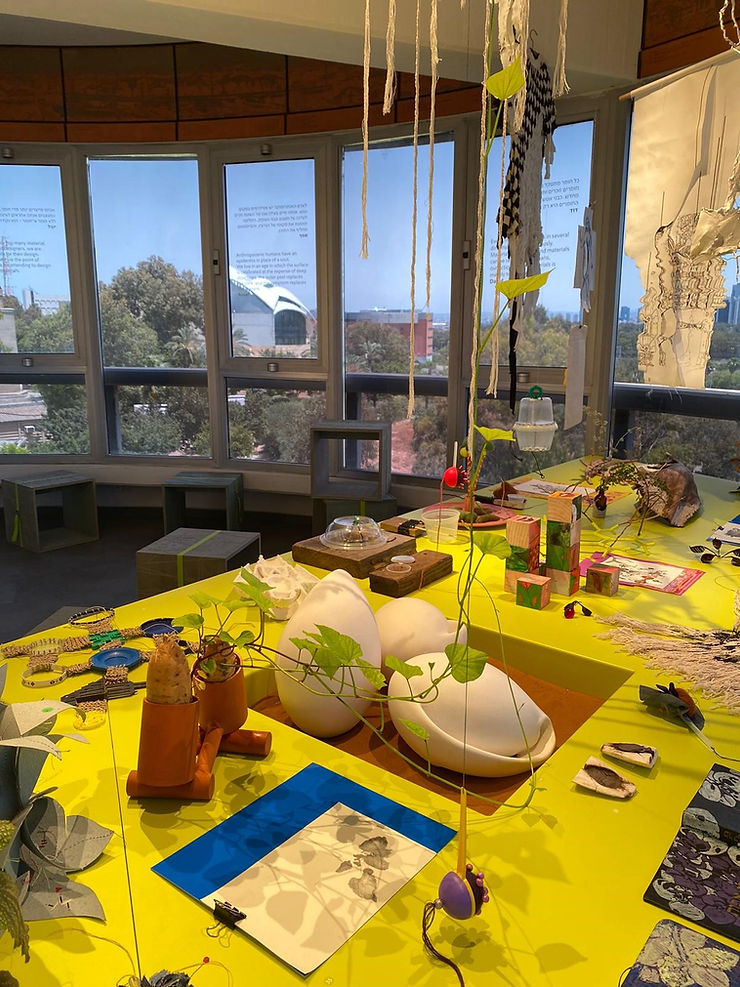

How does one organize a space that represents the idea of an “organism”? What experience did you want to transmit in designing the space?

Our organism is a representation of our idea of collaborative action. It is an abstract, multidimensional idea that is very difficult to reduce to a visual matrix or structure. Given these limitations, we tried to transmit a sense of concentration, of a happening, an ebullient life energy, density, perhaps even a bit of confusion, disorder, movement (not necessarily physical), change, an invitation, an energetic sphere that produces more questions than answers – the essence of our organism.

The choice of a table and 12 stools, whose location is constantly changing, represents the spirit of our meetings, which always took place around a table on which the objects we created mingled with food, dishes, drinks and conversation, as we moved around the table and amongst ourselves. The location of the table as bisecting/occupying the space seeks to rupture the environmental conventions that defines us (in this case, the architectural space), while forcing the viewers to be in movement, to change perspectives, to sit at the table or by the window or wherever they choose, dynamically positioning themselves in relation to the space we created. One of the nice things that happened in an unanticipated manner (although we spoke about it quite a bit while planning the exhibition), is that when one sits in the space and looks out the window, the landscape outside merges with the “landscape” created on the table, forming a fusion between interior and exterior that marvelously underscores this idea of our continual interaction with everything that is not us, not matter what we do and where we are. Our awareness as humans is accompanied by a responsibility to charging these interactions with both the human and the nonhuman elements of our environment with significance.

Will you continue working as a group?

Yes. We still don’t know what our next project will be, but we are certainly going to continue.

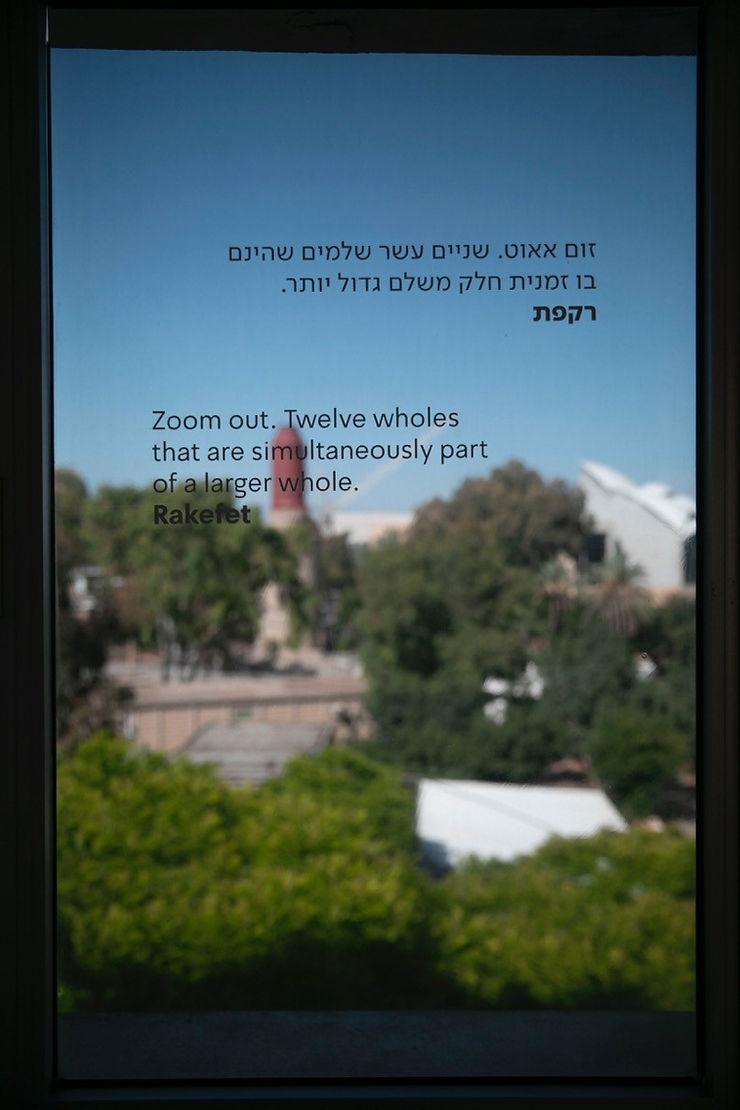

Zoom out. Twelve wholes that are simultaneously part of a larger whole.

Rakefet

This project was produced with the support of the Israel Lottery Council for Culture & Arts and the Rozen Center for Sustainability at Shenkar

More Articles

New Acquisitions: Gifts from the Tennenbaum Collection to the Glass Pavillion Over 70 glass items from the Rivka and Zvi Tennenbaum Collection have been donated to the Glass Pavilion in memory of their son, the flute player Yadin Tennenbaum, who was killed at the Suez Canal in the Yom Kippur War

18.04.24

New Acquisitions: Works Exhibited at the Biennale of Crafts & Design Some 60 artists whose works were exhibited at the Biennale of Crafts & Design held at the museum in 2020 and 2023 generously contributed their works to the collection of MUZA, Eretz Israel Museum, Tel Aviv

18.04.24

International Conference: DAY 1 – movies and lectures

24.01.22